The scientific community has long regarded Alzheimer's disease as one of the most perplexing medical mysteries of our time. For over a century, researchers have pursued countless avenues to understand its origins and develop effective treatments. Yet, despite billions of dollars invested in research, the disease remains incurable, and its underlying mechanisms are still hotly debated. A growing number of scientists now argue that the field may have taken a wrong turn decades ago, leading to a cascade of misguided hypotheses and failed clinical trials.

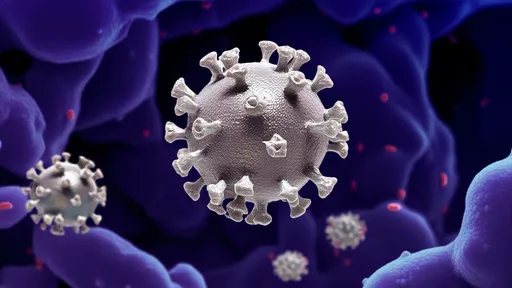

At the heart of this controversy lies the amyloid hypothesis, which has dominated Alzheimer's research since the 1980s. This theory posits that the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain is the primary cause of neuronal damage and cognitive decline. Pharmaceutical companies have poured resources into developing drugs that target these plaques, yet time and again, these treatments have shown little to no benefit in human trials. Some researchers now suggest that amyloid may be a symptom rather than the cause of the disease—a red herring that has led the scientific community down a fruitless path.

The origins of this misdirection can be traced back to the early 20th century, when German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer first identified abnormal protein deposits in the brain of a deceased patient with dementia. While his observations were meticulous, the interpretation of these findings may have been overly simplistic. Modern critics argue that the focus on amyloid plaques overshadowed other potential factors, such as chronic inflammation, vascular dysfunction, or metabolic disturbances. The scientific establishment's unwavering commitment to the amyloid theory created an echo chamber, stifling alternative approaches and dissenting voices.

One of the most troubling aspects of this century-long detour is the sheer scale of wasted resources. Billions of dollars have been funneled into amyloid-targeting therapies, while promising alternative research avenues struggled for funding. The recent approval of controversial drugs like aducanumab, which showed minimal clinical benefit despite reducing amyloid plaques, has only deepened the skepticism. Many experts now question whether regulatory agencies have lowered standards in desperation for any semblance of progress against this devastating disease.

The consequences of this potential misdirection extend beyond financial waste. Countless patients and their families have pinned their hopes on treatments that ultimately proved ineffective, while potentially viable alternatives languished in obscurity. The Alzheimer's research community now faces a critical juncture: whether to double down on the amyloid approach or to radically reconsider the fundamental assumptions that have guided the field for generations. Some researchers are already exploring new paradigms, such as the role of infections, environmental toxins, or the brain's immune system in neurodegeneration.

What makes this situation particularly tragic is that clues about alternative mechanisms were available decades ago but were largely ignored. Historical autopsy studies showed that many elderly individuals with significant amyloid buildup never developed dementia, while others with severe cognitive impairment had surprisingly few plaques. These anomalies were often dismissed as exceptions rather than challenges to the dominant theory. The scientific process, which ideally should be self-correcting, instead became entrenched in what some describe as a form of intellectual inertia.

The story of Alzheimer's research serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific dogma and the importance of maintaining intellectual flexibility. As the global population ages and the prevalence of dementia rises, the urgency for effective treatments has never been greater. The field now stands at a crossroads, with an opportunity to learn from past mistakes and embrace a more nuanced, multifaceted understanding of this complex disease. Whether the scientific community can overcome a century of entrenched thinking may determine if we finally make genuine progress against Alzheimer's or continue repeating the same costly errors.

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025