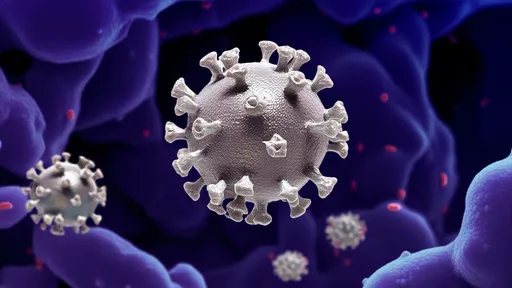

The world of viruses, often associated with disease and destruction, has unexpectedly become a source of aesthetic fascination. Under the lens of an electron microscope, these microscopic entities reveal intricate structures and mesmerizing patterns that challenge our traditional notions of beauty. What was once feared as invisible killers are now being appreciated as nature's most unexpected artists—creating a paradoxical intersection between science and art known as "viral aesthetics."

The concept of virus as art isn't merely about visual appeal; it forces us to confront the duality of their existence. These are organisms that can devastate human life, yet possess an undeniable structural elegance. The symmetrical protein coats of adenoviruses resemble geometric mosaics, while the helical symmetry of tobacco mosaic viruses creates hypnotic spirals that could easily be mistaken for avant-garde sculptures. This visual splendor exists independently of their biological function, creating what some researchers call "accidental masterpieces."

Electron microscopy has been the game-changer in this unusual artistic revelation. The technology's ability to magnify objects millions of times transforms viral particles into breathtaking landscapes. When false-colored for enhanced contrast, these images reveal surreal architectures: the bacteriophage with its lunar-lander-like structure, the influenza virus with its spiky corona resembling a medieval mace, or the HIV virus budding from cell membranes like some grotesque yet fascinating fruit. Scientists working with these images often report an uncanny sense of awe when first encountering these magnified views—a sentiment more commonly associated with art galleries than research laboratories.

The artistic quality isn't limited to static images. Advanced imaging techniques now allow scientists to create three-dimensional reconstructions and even animations of viral structures. Watching a rotavirus rotate reveals its wheel-like symmetry, while seeing herpes simplex virus particles assemble demonstrates an almost choreographed precision. These dynamic visualizations blur the line between scientific documentation and digital art installation, prompting some institutions to display them in science museums alongside traditional artworks.

This emerging appreciation has sparked debates in both scientific and artistic circles. Some virologists argue that aestheticizing pathogens risks trivializing their deadly nature, while others contend that understanding their visual complexity can lead to better public engagement with science. Contemporary artists have begun collaborating with microbiologists, using actual viral imagery as inspiration for installations that explore themes of vulnerability, interconnectedness, and the fragile balance between humans and microorganisms. The results are often unsettling yet beautiful—much like the viruses themselves.

Perhaps most intriguing is how viral aesthetics challenge our perception of scale and significance. These are structures measured in nanometers, invisible to the naked eye, yet when amplified reveal complexities that rival human-made designs. The HIV capsid's mathematical perfection, the fractal-like branching of filamentous viruses, or the almost floral arrangement of Ebola virus particles—all suggest an inherent visual logic that exists independently of human observation. It raises profound questions about whether beauty is an objective quality in nature or purely a human construct projected onto microscopic phenomena.

The false-coloring techniques applied to electron micrographs add another layer to this artistic dimension. Scientists assign colors based on structural features or chemical composition, creating palettes that range from eerily biological to psychedelically abstract. A single virus might be rendered in electric blues and fiery oranges not because those are its "real" colors (viruses are too small to reflect visible light), but because the coloration reveals functional zones or makes patterns more discernible. This artistic license transforms clinical images into visually striking compositions that circulate widely in both scientific publications and popular media.

Some institutions have begun curating collections of these images as art. The Wellcome Collection in London and the Micropolitan Museum in the Netherlands have exhibited viral microscopy alongside explanations of their biological significance. These exhibitions force viewers to reconcile their instinctive revulsion toward disease-causing agents with an involuntary admiration for their visual splendor. The cognitive dissonance created—simultaneously fearing and admiring the same object—may be the most powerful artistic statement these microscopic entities make.

As imaging technology advances, the viral aesthetic movement continues evolving. Cryo-electron microscopy now captures viruses in near-native states, revealing previously unseen details. Computational methods can simulate how viral structures interact with cells, creating animations that are both scientifically accurate and visually spectacular. Meanwhile, artists continue finding new ways to interpret these microscopic forms through sculpture, digital media, and even fashion design—with viral patterns inspiring everything from textile prints to architectural elements.

The phenomenon raises intriguing questions about the nature of art itself. If beauty exists in something as functionally destructive as a virus, does that suggest aesthetics operate independently of moral judgment? Can the tools of science become mediums for artistic expression when they reveal unexpected visual wonders? Viral aesthetics doesn't provide easy answers but offers a compelling new perspective on the intersection of science and art—one where the most feared invisible enemies become unlikely muses, and where cutting-edge technology reveals beauty in the most improbable places.

Ultimately, the appreciation of viral beauty doesn't diminish their danger any more than admiring a tornado's funnel cloud reduces its destructive power. But this peculiar intersection of virology and aesthetics serves an important purpose: it reminds us that nature's designs often transcend human categories of "good" and "bad," that complexity and threat can coexist with breathtaking elegance, and that even in the realm of the deadly, there exists visual poetry waiting to be uncovered by the curious eye.

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025

By /Jul 2, 2025